|

|||||

|

News

About Us

Membership

Events

Links

|

|

Cornell University's illustrated history of trade cards: Highlights from the Waxman Collection

Malcolm Shifrin

Every member of the Ephemera Society is familiar with the definition of ephemera as being 'the minor transient documents of everyday life', the last of several formulated by the society's founder, Maurice Rickards. As a definition, it seems a model of brevity and clarity, and in 1975, was certainly appropriate as an indication of what the newly formed society was all about. Even so, the wonderful collection at the Bodleian Library has been known since 1968 as the John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera (my emphasis). Johnson, who had been Printer to the University of Oxford, originally named his collection the Constance Meade Collection of Ephemeral Printing, perhaps to distinguish ephemeral printed matter from the more 'permanent' printed books and periodicals which were the products of his professional activity. Maurice, however, was defining ephemera for the passenger on the Clapham omnibus who, one must assume, would be unlikely to confuse Maurice's subject with that of a zoologist studying the genus ephemera. So he probably felt it unnecessary to modify the term 'documents' with any adjectival form of 'print'. At around the same time, a group of librarians from both sides of the Atlantic was struggling to revise the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules (AACR) which, in 1968, replaced the first international cataloguing code for books, originally published sixty years earlier. AACR, like its predecessor, was also primarily a code for cataloguing books, but with several additional chapters providing further codes for librarians cataloguing separate collections of materials such as sheet music, gramophone records, and films. So, in the early 1970s, this group of mainly book librarians was embarking on a project (some of them with obvious reluctance) to make a single code of cataloguing rules which were also hospitable to what were then known as 'non-book materials'. This was in response to the increasing demands of librarians in educational establishments, from university level to school level, whose book collections were being supplemented by gramophone recordings, slides, filmstrips, overhead projection transparencies, and occasional films. While Maurice was defining ephemera, these librarians were arguing over what exactly was a document. Was a pre-Windows™ program a document? Was a film a document and, if so, who was its author? How did one distinguish between a Betamax™ tape and a VHS™ tape? Do we even remember either of these video formats today? And when the Centre for Ephemera Studies was formed at Reading University in 1993, one of its aims was the standardisation of cataloguing rules for ephemera. All of this rather surprisingly came to mind when I recently discovered a fascinating new series of website pages about trade cards. For, as many of us will have discovered all too frequently, what can be more ephemeral than the pages of a website?

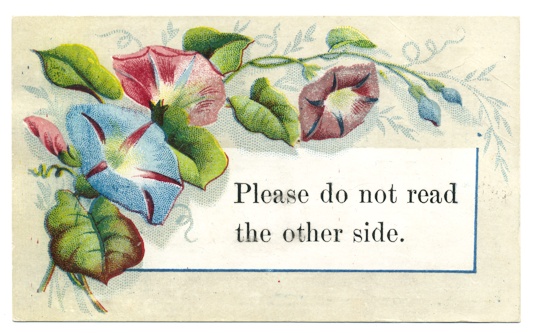

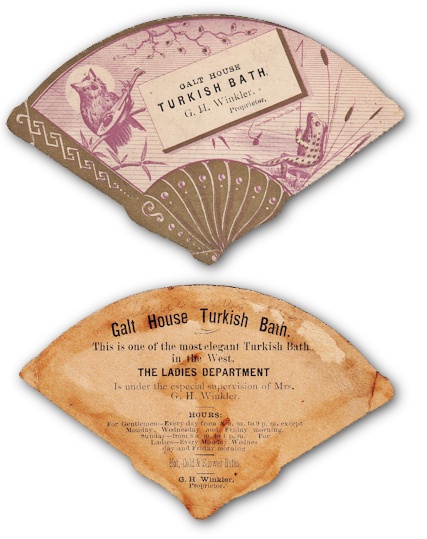

But in a time of constant cuts, who knows how long these will survive, or whether the exponentially expanding amount of material generated will need to be weeded, perhaps even by an algorithm. Which led me, almost immediately, to write to the library's Reference Coordinator to ask whether there were any plans to publish the pages as a traditional printed booklet. Perhaps one way to encourage the retention of such pages is to make them more widely known by reviewing them. But although The Ephemerist regularly reviews books, I can't remember a website review so far, though they have been noted, and are sometimes included in article references. What is an absolute certainty is that Trade cards: an illustrated history is a delightful account, beautifully illustrated, of cards about the food and culinary trade. I am a retired librarian and, more recently, a historian, rather than an ephemerist, and first came across American trade cards when researching my book Victorian Turkish baths. I found some cards on eBay and was able to purchase a few, discovering, much to my surprise, that there were not only rectangular cards, but shaped ones also.

Knowing nothing about trade cards, I turned to Maurice's indispensable reference work The encyclopedia of ephemera (BL, 2000) and found everything I needed to know at the time I most needed it. Returning to it now, however, I am reminded that the entry on trade cards, covering only two out of nearly four hundred pages, and dealing with but one of several hundred different types of ephemera, was necessarily limited in the number of images which could be included. However, these do include three cards aptly shaped to reflect their subjects, a cotton reel, a pair of gloves, and a sack of salt.

Although the article is followed by a short list of trade card collections, its publication precluded mention of the Waxman Collection since this was only donated to Cornell fifteen years later. So the online exhibition will be of special interest, not only to trade card collectors, but also those who collect other food-related ephemera. The Waxman Collection of Food and Culinary Trade Cards (to give its full title) was assembled by Nachman (Nach) Waxman, founder of Kitchen Art & Letters, the well-known New York City bookshop specialising in the literature of food and drink. It contains around 6,500 printed advertising cards from the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Although the cards are mainly of American origin, there are others from some western European countries, including France, Germany, and Britain.

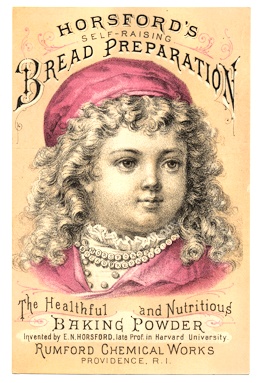

In 2015, the collection was donated to Cornell University Library by Nach and Maron Waxman, joining others in the library's Division of Rare & Manuscript Collections which treat the history of food and its related subjects. They are invaluable, not only to scholars of social history, but also to those studying specialised areas of the food industry, and to those working on the history of colour printing, advertising and food marketing. The online exhibition is divided in to three sections, the first of which is called Introducing trade cards. This begins with a short history of trade cards beginning with the period around 1870 and progressing from the stage when a second colour was added to black and white business cards, through the fresh opportunities offered by the development of chromolithography, until the beginning of the twentieth century, when large-scale colour printing led to the replacement of trade cards by magazines and other forms of advertising. This page alone includes captioned images of eighteen cards. But not only can each image be enlarged to full screen size, but by moving the cursor over the enlarged image one can zoom over individual parts. There are multiple views of some cards, where a printer's stock card has been overprinted with the advertisements of different traders.

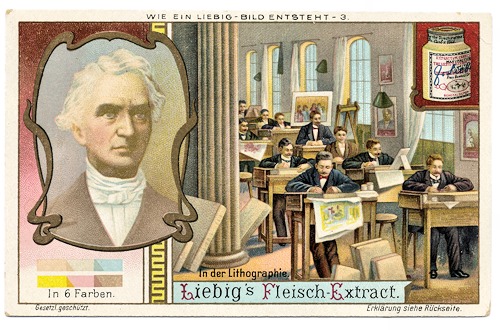

Most un-American looking is a Heinz chef about to step out of a die-cut pickle-shaped card. Every page on the site has images which can be enlarged and are zoomable. The second page of this section deals with the printing of trade cards and features a set of six Liebig Meat Extract cards demonstrating the chromolithography process used to print them. The cards show the different stages of the process, each containing a full colour image depicting part of the process, together with an inset vignette of Liebig himself, the first showing three passes of the stone for the first three colours, and the last showing the full twelve colour and black version of the vignette. (The third of the cards is shown here.)

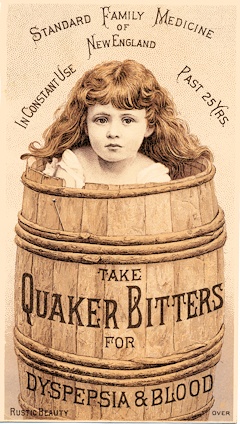

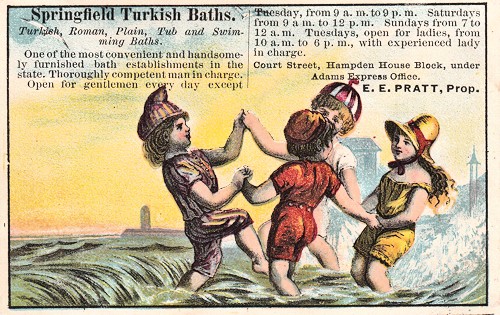

The second section is the main exhibition itself, divided into six parts headed: Fashion and Style, Recreation and the Cultured Life, Virtues and Values, Men and Women, Ourselves and 'Others', and Food and Health, although the latter does not include Turkish baths, even though, at this time, these were often advertised as being aids to slimming.

In the fifth part, Ourselves depicts typically middle class Americans, while 'Others' shows people of colour, together with immigrants, and people from Ireland and China. Altogether the exhibition section includes coloured images of over eighty cards. What makes them particularly interesting for print and social historians is that, although the traders using the cards are all connected with some aspect of food, the actual images on the cards include anything from pieces of china to the deck of a luxury liner, and from an early automobile to children playing on the beach, or innocently kissing each other. Finally there is a section with further information about the Waxman Collection, and a short reading list. At present there is no guide to the entire range of cards in the collection, but it is intended to provide one in the near future. A wonderful website, surely guaranteed to delight collectors of ephemera on any subject. Copyright © Malcolm Shifrin 2017. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

|

Home | News | About Us | Membership | Events | Links | Contact | Item of the month | Articles |

| Copyright © The Ephemera Society 2025. All Rights Reserved. |

Hopefully, because these particular pages were published by Cornell University Library's Division of Rare & Manuscript Collections, and form just one of fifty online exhibitions on their website, they will prove to be more permanent. There are now, after all, a few website archives such as the

Hopefully, because these particular pages were published by Cornell University Library's Division of Rare & Manuscript Collections, and form just one of fifty online exhibitions on their website, they will prove to be more permanent. There are now, after all, a few website archives such as the

Another card, depicts a windmill, the card itself having flaps which can be opened to show sacks of flour inside, together with a view of the whole mill area.

Another card, depicts a windmill, the card itself having flaps which can be opened to show sacks of flour inside, together with a view of the whole mill area.

In turn, each of these parts is subdivided into two or three. So Fashion and Style, for instance, has pages on What to Wear, Home Décor, and Hair is Important. While Food and Health includes Food for Young and Old, and Miracle Remedies.

In turn, each of these parts is subdivided into two or three. So Fashion and Style, for instance, has pages on What to Wear, Home Décor, and Hair is Important. While Food and Health includes Food for Young and Old, and Miracle Remedies.