|

|

| News About Us Membership Events Links |

|

The Riddle of the Carte-de-Visite

Graham Hudson exposes the other side of carte-de-visite photographs. Among collectors the term passes without comment — carte-de-visite. At antiques fairs and collectors’ markets they are ubiquitous, these little photographs, on the one side perhaps a fashionable young man in elegant topper or young woman in voluminous crinoline, or (less commonly) a small family group: on the other the elaborately presented studio address of the photographer. As records of costume they are invaluable, but as more personal records they are not without poignancy. In old shoe boxes amid the pots and pans of the boot fair, divested now of the family context that once brought them into being, we buy them at 50p a card. Who are these people whose eyes now touch ours across the years? We cannot know.

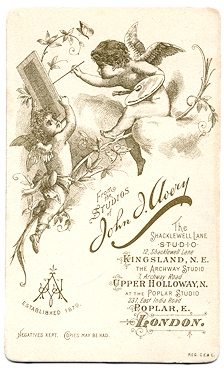

But why carte-de-visite, literally ‘visiting card’? In an article in Antiques Journal Lou McCulloch noted ‘The mounted card was approximately 2½ by 4 inches, slightly larger than a calling card, and, correspondingly received the French equivalent for a visiting card as its nom de plume’, McCulloch thus assuming the term adopted through simple association of scale. Yet if one puts a carte-de-visite photograph actually side by side with a range of nineteenth-century calling cards, then the difference in the simple look of them makes such a transference of nomenclature unlikely. The great populariser of the carte-de-visite was André Disdéri, who in 1854 was granted patent for a means whereby several smaller images could be exposed on to a single 10 x 8in plate, thus reducing overall processing costs. It is not clear however on what Disdéri’s patent was based, for central to the process must have been the camera, and the camera Disdéri first used was one invented by Antoine Claudet, and shown by him at the Great Exhibition in 1851. Claudet’s instrument. the ‘multiplying camera-obscura’, had a plate holder ‘Which could be mechanically moved both across and down to allow different areas of the emulsion to be covered by successive exposures through the same lens, to represent on the same surface a number of different pictures, or the same in various aspects, the portraits of several persons, & c.’ Later cameras adopted by carte-de-visite photographers included those with four independent lenses which, working with a simple shift mechanism, could double up to take the usual set of eight images on the one plate, and those of the London manufacturer Routledge, which worked on the Claudet principle but with which no fewer than twelve cartes could be taken. The great period for the carte-de-visite was from 1859 to the later 1860s. It was in May 1859 that Napoleon III riding at the head of his troops, actually halted the French army en route to the war in Austria whilst he called at Disdéri’s Paris studio. The Emperor had shrewdly realised how effective as personal publicity such cheap portraits would be among the populace; and what the Emperor did the whole of fashionable Paris was quick to emulate. Disdéri made a fortune, opening studios in Toulon, Madrid and London. At the height of the craze, in 1866, it was estimated that between three and four hundred million of the small-scale photographs were sold in England alone. But after that year the fashion went into quick decline, though the carte-de-visite as the accepted format for run-of-the-mill family record was to last well into the century. Ergo those countless little sepias we find today in every fleamarket. They are worth collecting, and not least for the sake of their often richly decorated backs, photographers in effect turning their very products into tradesmen’s cards for the businesses that produced them. Most frequently the backs were printed by lithography, exploiting the freedom and intricacy in design afforded by the process, and rich in invention though they were it is not uncommon for the collector to come across the same basic imagery employed on the photo backs of quite different establishments. The designs were created of course not by the photographers but by commercial printers, who had access to ready-drawn imagery in the form of stock litho transfers in the same way that letterpress printers had the facility of stock blocks, and it is these stock motifs that one finds recurring.

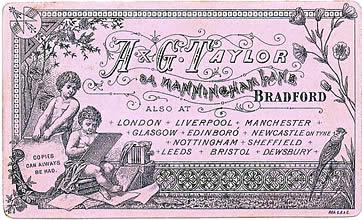

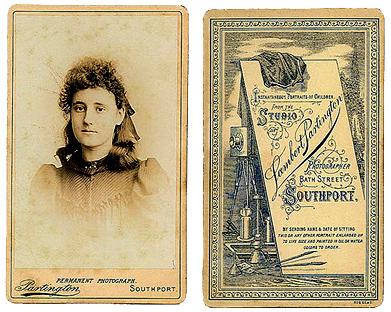

Though photography was in very essence part and parcel of the science and technology of the period - collodion, silver nitrate, anastigmatic lenses et al - the theme of photo-back imagery is essentially that of ‘Art’. There is scarce a chemical in sight. The underlying art theme of A & G Taylor’s photo-back illustrated here, with its flowers, birds, abstract patterning and one little putto actually creating a picture by drawing is not untypical, and that the imagery in this case does include an incidental camera is sufficiently uncommon to put this example into a distinct sub-category known to collectors as a ‘camera-back’. Rare indeed is a design such as that of Lambert Partington of Southport showing the whole paraphernalia - camera, dark slide, developing dish, retouching brushes and even painted studio backcloth-virtually the complete kit.

But still, ‘visiting card’?

Could these little photographs ever actually have been so used? I had this

question in mind for a long time. Helmut and Alison Gernsheim in their History

of Photography quote Ernest Lacan, editor of La Lumiére

writing in the issue of 28 October 1854 regarding two Parisian amateurs

E Delessert and Count Aguado who, it appears had at least the idea

of photographic calling cards: However, in 1857, photographer T. Bullock of Macclesfield was actually advertising address cards ‘with a splendid photograph on the reverse side’ (have any surviving examples been located, one wonders?) and a chance find at an Ephemera Society bazaar was the carte of Charles Tomlinson, of New Britain, Connecticut, where, with its combination of tasteful engraver’s black-letter and discreet script, the back has all the appearance of a gentleman’s calling card rather than the up-front display of the photographer.

The clincher though must be the Punch cartoon of 1862, only recently noticed. There is your young man about town, young Tomkins, card case in hand, attempting to leave his undoubted carte-de-visite . The joke is that the little photograph, scarce glanced at by the flunkey, is taken for a mere tradesman’s card and Tomkins peremptorily dismissed. Evidently the fashion of the carte as card was uncommon even then. Thus a little light is thrown on a forgotten and ephemeral fashion. How briefly must those cartes have manifested on the card trays of those who made and received calls, to have left so little impression on the historic record and in the collections of the ephemerist. As for Disdéri, reputed in 1861 to have been the richest photographer in the world, money ran through his fingers. With the decline in the carte-de-visite craze his fortunes too went into decline and he ended his career as a beach photographer in Nice, dying in the poor house there in 1890. Copyright © 2003. All Rights reserved.

|

|

|

Home | News | About Us | Membership | Events | Links | Contact | Item of the month | Articles |

| Copyright © The Ephemera Society 2025. All Rights Reserved. |