|

|

|

News

About Us

Membership

Events

Links

|

|

Graham Hudson examines the imagery of Knaresborough’s premier tourist character, the prophetess Mother Shipton. Visiting the Knaresborough Dropping Well in 1697, Celia Fiennes wrote in her journal ‘and this water as it runns and where it lyes in the hollows of the rocks does turn moss and wood into Stone ...I took Moss my self from thence which is all crisp'd and perfect Stone ... the whole rock is continually dropping with water besides the showering from the top which ever runns, and this is called the dropping well’1. Thus did Celia Fiennes observe the petrifying qualities of this North Yorkshire town's premier tourist site; yet, curiously, she made no mention of Knaresborough’s premier tourist character, the prophetess Mother Shipton.

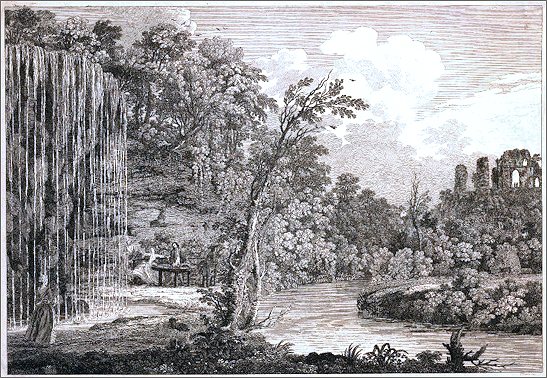

Engraving c1771, closely copied from an earlier engraving of 1746-7 by Francis Vivares after Thomas Smith, depicting the scene much as Celia Fiennes knew it.

Ursula Southeil - later through marriage, Mother Shipton

- is said to have been born in the cave adjacent to the Dropping Well around

1488. The earliest publication of her prophecies is a pamphlet printed in

York as late as 1641, by which date, not surprisingly perhaps, most of its

predictions had been fulfilled. In 1684 Richard Head published The

Life and Death of Mother Shipton a garbled version of which subsequently

appeared in 1862. This later edition included some additional prophecies, such as: The author Charles Hindley owned up to the concoction of these retrospective prophecies in 1873, but even so, when 1881 came round, there was in the words of the Encyclopaedia Britannica ‘the most poignant alarm throughout rural England ... the people deserting their houses, and spending the night in prayer in the fields, churches and chapels’. In my copy of The Life and Prophecies of Ursula Sontheil [sic] Better Known as Mother Shipton, Dropping Well Estate Ltd, undated but certainly later than the 1880s, I note earth’s doom subsequently quoted at ‘Nineteen Hundred and Ninety One’, which fortunately we have now safely passed. Mother Shipton’s Prophecy Book (Diana Windsor, lan Wolverson, Astroquail Ltd, 1988) countenances no similar updating and omits the prophecy altogether.

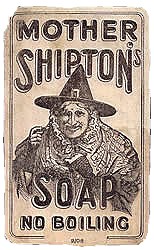

The old lady shown on Ideas as to Mother Shipton’s appearance have varied with the context of their description. Richard Head has it that ‘her head was long, with sharp fíery eyes, her nose of an incredible and unproportionate length, having many crooks and turnings, adorned with many strange pimples of divers colours, as red, blue, and dirt ...’ the soap-wrapper block illustrated here ‘Mother Shipton’s Soap No Boiling’ is altogether more prepossessing - a benign granny in a pointy hat.

The waters of the Dropping Well do ‘turn things into stone’. In the museum you can see a shoe donated for petrifícation by the late Queen Mary, a lace parasol turned to stone in the 1890s, and a petrifíed top hat which one can actually try on. The size is about six & seven eighths inches and it is very heavy. The waters of the well are rich in calcium bicarbonate. Decrease in pressure as the water emerges from a spring above the Dropping Well causes an out-gassing of carbon dioxide with the consequent freeing of calcium carbonate, otherwise known as calcite. Once chemically free, the calcite tends to crystallise on what ever the water then encounters; and today there are a host of things hung up for the water to encounter as it splashes down into the pool below 2. Stuffed birds and animals need up to 18 months to take on their coating of stony calcite. Cardigans and similar knitwear require but six to eight. Teddy bears (a current favourite) will I reckon take somewhere between the two. There were 61 teddies suspended in various stages of petrifícation, some already fíxed and stony, others in the early stages and still more or less ginger, at the time of my visit in August 2001. The Knaresborough Dropping Well was the subject of a painting by the 18th century topographical artist Thomas Smith of Derby, who engaged Francis Vivares to make an engraving after his picture in 1746-7, dedicating the plate to the estate’s owner Sir Henry Slingsby3. The same image was subsequently re-engraved, by another hand and on a smaller scale, as an illustration for The Complete English Traveller published in 1771. Here, now fíxed for ever in paint and line, a lady and gentleman relax at a rustic table, another gentleman contemplates the prospect of Knaresborough Castle across the Nidd; the lady gestures, and a maid approaches by the ever falling waters. This is virtually the Dropping Well as Celia Fiennes had known it a generation or more before, when she could write: ‘...there is an arbour and the Company used to come and eat a Supper there in the evening, to have the pleaseing prospect, and the murmuring shower to divert their eare’. Other things are worthy our notice in this scene. First - no representation of Mother Shipton’s Cave, though it would have been in plain sight from Smith's viewpoint, a curious omission in the age of the picturesque. Then equally surprisingly there are no things hung about the well for petrifícation. Celia Fiennes in 1697 did observe of the Dropping Well that, besides moss, ‘in a good space of tyme it will harden Ribon like Stone or any thing else’ [my emphasis], suggesting at least the occasional introduction of items for petrifícation in those early days, but nothing on the scale that the visitor sees today.

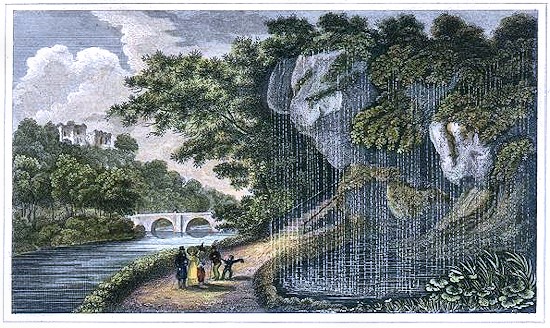

The Dropping Well at Knaresborough. Image courtesy of antiqueprints.com In 1829 J Hinton of Warwick Square, London, published an engraving by J Shury after a drawing by N Whittock showing the Dropping Well from the opposite viewpoint. Again objects hung up for petrifícation are notable by their absence. That such would have been overlooked or disregarded by the artist seems inconceivable, so one concludes that the practice was not established even by this date. So when was it? Certainly by 1855, in which year Rock & Co published a charming vignette of the Dropping Well on a sheet of their illustrated writing paper. Examining the fíne detail with a magnifying glass it is just possible to make out the shapes of various items suspended beneath the dropping waters.

To stand in the entrance to Mother Shipton’s Cave today with Shury’s engraving in hand, looking out on the scene as Whittock did when he made his sketch, is an education in the mind-set of the picturesque. The Dropping Well is impressive today, but the tiny family in the engraving (the adults can be no more than 18 inches tall) make of it a lofty crag. The castle is worthy of note too. There is a castle at Knaresborough, but in vain will you look for it down-river towards Low Bridge. Thomas South’s view, looking up-river, is the more correct, but even then Smith had to indulge in a 45° westward shift of the ruins to get them into view. The last word on the Dropping Well can go to the Field correspondent Francis Buckland, who in his Curiosities of Natural History describes taking the footpath to the well, and there beholding ‘a curious frowning rock suspended with a peculiar assortment of objects’. According to the little girl who directed Buckland to the spot, in those days the petrifications included ‘a pumpkin, a small hotter and a nedgeog’4. Mother Shipton’s Cave, the Dropping Well, and there is a genuine Wishing Well too, are well worth your visit. From Knaresborough’s High Bridge one follows Sir Henry Slingsby’s Walk and then descends by the steps that Buckland took down to the bank of the Nidd. There, it is all glistening stone and refulgent green moss. Long streamers of ivy hang pendant on the rock faces, and endlessly there is the trickle, splash and cascade of water. Things here can have changed but little since Celia’s day, when she could lay down her pen and then she and her company turn to supper, with all the while ‘the murmuring shower to divert their eare’. Notes

Copyright © Graham Hudson 2003. All Rights reserved.

|

|

|

Home | News | About Us | Membership | Events | Links | Contact | Item of the month | Articles |

| Copyright © The Ephemera Society 2025. All Rights Reserved. |

The present owners of the estate are ambiguous: the effigy shown

in their Historia Museum is defínitely in the Richard Head old crone tradition,

whilst the image on their publicity leaflet is more that of the rosy cheeked

super-gran.

The present owners of the estate are ambiguous: the effigy shown

in their Historia Museum is defínitely in the Richard Head old crone tradition,

whilst the image on their publicity leaflet is more that of the rosy cheeked

super-gran.